Susan B. Anthony’s Santa Barbara Sojourn Was Just One Stop on Rough Road to Get the Vote

In the month leading up to this week’s election, I spent an unhealthy amount of time debating with girlfriends on Facebook about political candidates. Some of these women denounced attack ads, others bristled at the mess of campaign financing, and still others upbraided me for insisting that Bloomberg is just another tantrum-prone manbaby. Sometimes our arguments got heated — and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

This is what we do — the informed, opinionated, engaged women of our town. Of our county and state. Of our nation. We think about issues and develop viewpoints around them: Race-based policing. Cannabis growth. The housing crisis.

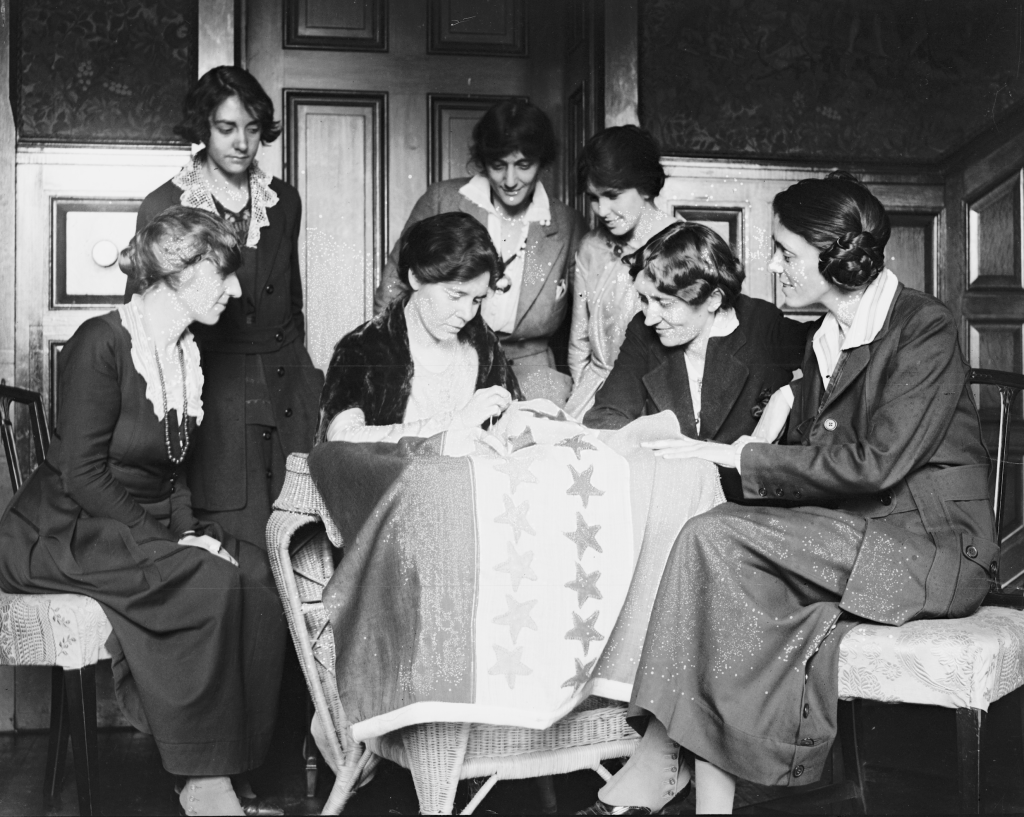

In all of our weighty pondering, though, there’s one important thing that we rarely think about: the onerous work it took to earn us the right to vote exactly 100 years ago. Putting our opinions into action by means of the ballot is a privilege we take for granted now. It’s so assumed, so obviously just, and so second nature that it’s almost offensive to have to be grateful for it, isn’t it?

In the last two presidential elections, women have outvoted men by 10 million ballots. Yet this right was never given to us — not by anyone, not for a hot minute. It was fought for and hard won over 70 relentless years by courageous women and some principled men who flat-out refused to give up.

Did you know that the most famous of those soldiers, Susan B. Anthony, came to Santa Barbara to implore our town to support women’s suffrage in 1896 — a full 24 years before the 19th Amendment would be passed nationally? Anthony, whose don’t-eff-with-me face later graced the U.S. silver dollar, was a straight-up rock star — even at age 70. As she made her way down the West Coast to entreat Californians to invite women to the state polls, 500 hollering fans greeted her in Nipomo. More than 1,000 gathered to welcome her in Santa Maria, carrying her from the train to a stage. She had to make an unexpected stop in Los Alamos to placate the masses who gathered to see her there.

When she finally reached the South Coast, she took to the stage at the Lobero Theatre and spoke before a rowdy crowd.

“You have given her all the other rights under the law. You have educated her. And yet you deny her the right to respect herself and to command the respect of others. Women must have the ballot to fight the battles in the field of labor!” Anthony insisted, according to a history column in a 1971 News-Press. “Why not right a wrong and go the full length of giving woman the ballot?”

“We will! We will!” cried the audience, and Anthony — known for her wit — replied, “Good for you. I knew Santa Barbara was going to give us equal suffrage. The head under the bonnet should be made under the law as good as the bald head.”

The measure was defeated in California that year — but Santa Barbara kept its promise, voting 2,015 to 1,471 to let women vote. Voters in cosmopolitan San Francisco are the ones who ultimately struck it down.

But it wasn’t unusual for a single state to share such divergent points of view around suffrage. In fact, Elaine Weiss’s 2018 page-turner The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote documents the suffragettes’ dramatic and painstaking machinations to convince the Tennessee legislature to sign on as the final state needed to ratify the 19th amendment in 1920.

Weiss tells how opponents, known as the “antis,” argued that women — who at the time couldn’t own property, didn’t have custody of their own children, and, if married and employed, didn’t even technically own the wages they brought home — would be better served leaving government to their menfolk. They should focus on their families and homes, traditionalists said, rather than sullying their delicate sensitivities by mucking around in the putrid waters of politics.

“I’d rather see my daughter in a coffin than at the polls,” one father said in an Arkansas debate.

Proponents, known as the “suffs,” were pelted with rotten food, arrested, and threatened with bodily harm in the days before that final Nashville vote. One had tubes shoved down her throat and was force-fed by authorities while staging a hunger strike. An Oklahoma suff ignored her doctor’s orders to stay home with the Spanish flu, instead making an impassioned speech at a rally — and dying two days later.

The Rough Road to Vote

I confess that for a woman who likes to spout off about our laws and elected loons, I took my voting right for granted. But no more. In reading Weiss’s book, I learned some fascinating things that I will surely chew on when marking my ballot forever after.

Republicans used to be cool.

Sure, Democrats may be the feminist favorite now, but it was the Republicans — back when the Party of Lincoln stood for something other than white nationalism, Puritanical values, and billionaire tax exemptions — that really pushed suffrage through the Senate, with 76 percent of Republican senators voting in favor, and 60 percent of Democrats voting against.

Politics has always been nasty.

Much as we’d like to believe that lofty ideals and divine grit can win a noble fight, it actually takes some unpleasant wheeling and dealing to get things done in our government. In order to prove that women had a place in politics, the suffragettes had to not only play countless savage rounds of the Political Game but also crush it. And they did. But not without casualties. Susan B. Anthony was an abolitionist and friends with Frederick Douglass, who championed women’s suffrage all his life. But the 15th Amendment, giving black men the right to vote 50 years before any women, saw a rift in their alliance. “I will cut off this right arm of mine before I will ever work for or demand the ballot for the Negro and not for the woman,” Anthony said, proving that even heroes can be asshats.

Nobody wins a fight solo.

The women leading the suffrage movement were undoubtedly fierce, but they simply couldn’t have done it without help from those who were already in the privileged class. Those who already had a voice. Namely, men. Because a fair number of fellas respected women, spoke their consciences, and advocated for women, we can now be heard. Let’s remember that we’re now obligated to use our voices to speak up for others who aren’t being heard.

It could have gone either way. Truly.

Although Anthony was often quoted as saying, “Failure is impossible!” the final decision in Tennessee — the 36th state needed to ratify — was won by a single vote. Senator Harry Burn changed his vote to “aye” because his mother had implored him to. Thank you, Mrs. Burn. And props, Harry.

Hear Her Roar

California actually got a chance to vote on suffrage again in 1911, nine years before the nation as a whole did. Susan B. Anthony was dead, and Santa Barbara/Montecito architect Francis Townsend Underhill took it upon himself to warn his fellow residents that allowing women into politics would spell the doom of men and all the things they hold dear. “The normal male should hesitate before deliberately putting a noose around his own neck,” he wrote, according to the Montecito Journal. “The feminine mind is illogical and inclined to hysterical conclusions,” he added. “Be not overcome by subtle arguments from the mouths of silver-tongued matrons!”

Still, the measure passed by 76 votes in Santa Barbara, 200 in the county, and 3,000 statewide. California became the sixth state to invite women to vote alongside men — and more local women did so than was expected. Among the first to register was 94-year-old Jane McMartin.

So, I vow to remember Jane and her excitement the next time I receive heaps of campaign propaganda in my mailbox. To tip my hat to Harry Burn and his mama as I uncap my pen and set about expressing my viewpoint on a ballot. To never again slap an “I voted” sticker on my bosom without acknowledging the flawed but fierce Anthony and her compatriots, who toiled for the better part of a century so that … well, so that my gal pals and I could squabble over our electeds on social media.

Girlfriend, they don’t call it suffrage for nothin’.